By Glen Huntley

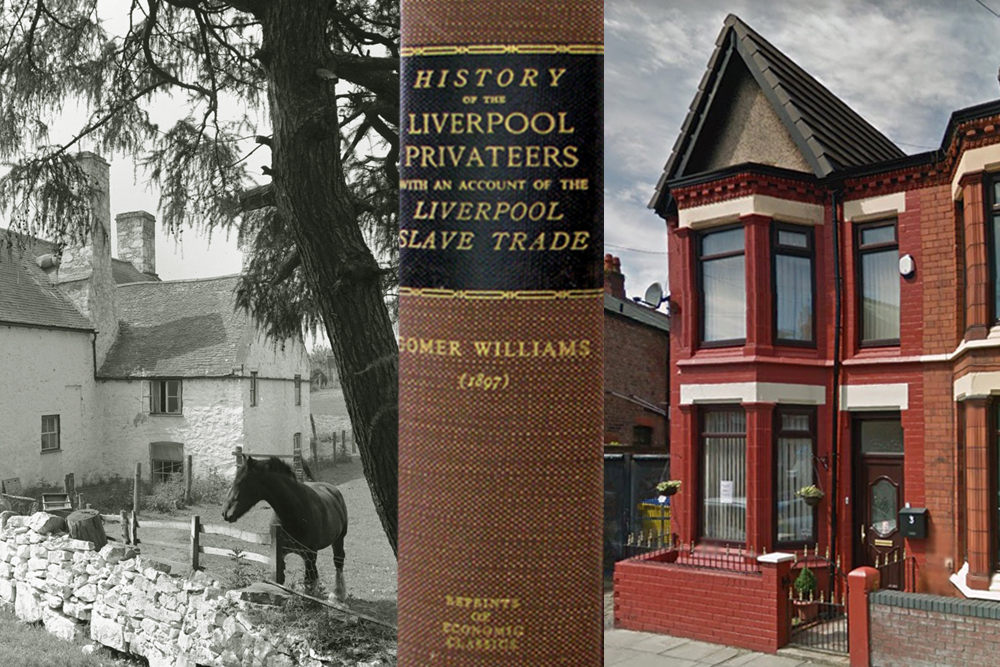

In 1897, Gomer Williams’ ground-breaking book History of the Liverpool privateers and letters of Marque with an account of the Liverpool slave trade was published. Ever since it has become one of the most referenced works in any book on the subjects. But what is known of the man who wrote it? Apparently next to nothing. We tell his surprising life-story and locate some of his surviving homes in Liverpool.

In the process we try and solve the mystery of another famous book Liverpool & Slavery, and attempt to discover the secret identity of its author known only as ‘Dicky Sam’.

For anyone new to Gomer Williams’ book, the importance of the work can be witnessed by searching for his name in the Internet Archive, there you will just a selection of the thousands of times his pioneering work has been referenced since it was published in 1897:

https://archive.org/search.php?query=%22gomer+williams%22&sin=TXT&page=6

You can read the first edition of the book below.

As the title suggests the book deals with two aspects of Liverpool’s history. The first part (representing most of the book) is devoted to Privateers. These were private individuals given license from the sovereign to attack and plunder enemy ships (basically pirates with paperwork). The letter of Marque they were given was issued by the Admiralty.

The clipping below appeared in the Manchester Mercury 5th July 1757. It is a comparison of the French ships recently taken by Liverpool privateers and the Liverpool-owned ships that had been taken. The Liverpool ships were computed to be worth £70,000 (about £13 million today). The article warns that ‘unless some Ships of War be stationed in the north Channels, the Liverpool trade will be inevitably runied’. Also mentioned is a ship taken by the famous Captain William Hutchinson of Liverpool. This was on the maiden voyage of his ship Liverpool. Between June and November 1757 alone the Liverpool would take a further 9 ships, and another 7 the following year.

The second part of the book deals with Liverpool’s involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Williams covered it in far greater depth than ever before.

A good synopsis appeared in a review in the Anti-Slavery Reporter and Aborigines’ Friend in December 1897.

This voluminous and most interesting volume of 700 pages is well worth studying by all who wish to be informed how, during the past century and up to 1807, England enriched herself by trading in human flesh, and how London, Bristol, and Liverpool, sent forth their merchant craft to buy the wretched natives of West Africa, and transport them for sale to the sugar planters of the West Indies. It has often been said that every brick in Liverpool has been cemented by human blood, and in this respect Bristol does not lag far behind. Those who study the history of England should make themselves acquainted with Mr. GOMER WILLIAMS’s remarkable book, for it gives a picture of organised greed and cruelty which, in our more refined days, seems almost incredible.

Anti-Slavery Reporter and Aborigines’ Friend. November-December 1897

This volume is divided into two parts, the first of which is the more bulky, and deals with privateers and letters of marque during the Seven Years’ War, the American War of Independence, the Wars of the French Revolution.

Research based on original documents

Gomer points out in the preface that he painstakingly sourced original material wherever possible. If he had to use a secondary source he supplied a footnote (we’ll come to that claim later).

This marked a great improvement to an earlier publication by an anonymous author, written under the pseudonym ‘A genuine Dicky Sam’ entitled Liverpool and Slavery. This was published by Adam Bowker & Son in 1884, with a print run of only 500. This earlier book often neglected to name his sources and in some cases appears to have invented some facts, and possibly even at least one newspaper clipping of an auction of an enslaved person. This is a shame as there are plenty more he could have used that appeared in the Liverpool press, we can only presume not all of these were available to view at the time.

Who was Gomer Williams?

The book itself tells us nothing of the author, indeed his life story appears has been somewhat of a mystery. The preface of the 2004 reprint of the book has only the following information about Gomer’s life:-

Williams (b. 1847?) was a writer in Liverpool, but apparently not a very successful one. This history, published in 1897 by William Heinemann in London and Edward Howell in Liverpool, seems to be his only published book.

2004 reprint

Not the best of biographies we’re sure you’ll agree, even his birth date has a question mark!

When Gomer died he was little known, an obituary that was published in the Welsh newspaper Y Brython in 1917 commented that it would be sad if “he should slip away without a hint of his work or abilities’.

We set out to answer some questions; What academic background did Gomer have? Why did he choose those subjects? Was it really his only work? Was he a Liverpool-born man or Welsh like his name implies?

As we were close to finishing the research this post we discovered that a two page article about Gomer had appeared in Spring 2020 edition of the long-running Welsh language magazine Y Casglwr. The article, including a short biography, was written by Mai Roberts and helped to confirm some aspects of his life.

For an author and historian renowned for such a serious work, often referenced by academics, the life-story of Gomer Williams is far from dull.

A complete biography of Gomer Williams

Early life

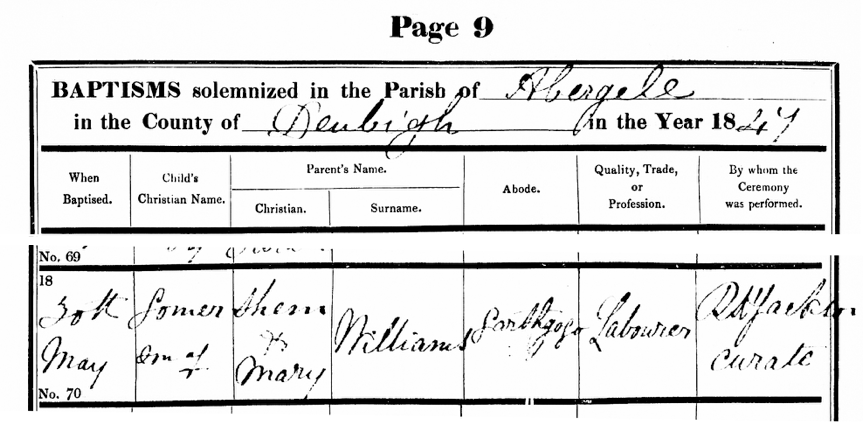

Gomer Williams was born at Garth-gogof and was baptised on the 30th May 1847 and his father Shem was listed as a labourer.

The marriage record of his parents shows that his mother Mary’s maiden name was Jones. Shem was actually a miner, following the trade of his father Edward (shown in 1851 as a time keeper at the nearby Llanddulas Lime Rocks quarry). Although Shem was working-class, his signature shows he could write. Mary on the other hand was illiterate and signed her name with an X. This was not at all unusual, it’s probably more unusual for the time that his father could write.

(For more information about Gomer’s early childhood home, see section: Gomer’s childhood inspiration for the stories)

By the census of 1851, the Williams family are living nearby, at the house of Mary’s father Robert, a widowed weaver, born in 1776. Mary and her father (already widowed) were living there ten years previously as shown on the 1841 census.

By 1851, Gomer’s father had left the quarry and is listed as a gardener. The Williams family house is part of a group named ‘Pant’ (Welsh for dingle) and is close to Garth-gogof he was born. It is possibly these farmhouses which are shown as Pant Idda in the 19th century.

A minimal education

Remarkably for such an accomplished author, Gomer left school before the age of 14 and appears to have had no further education. Yet, in 1861 Gomer had managed to avoid the dangerous occupation of his father and grandfather, and instead he chose a job in retail. The census shows he had left home and was working as an apprentice in a draper’s (cloth merchants) at Bradford House, Market Street. Abergele. Going by the census this was before the hotel and two doors from Medical Hall. The likeliest building therefor is this one.

Image: Abergele Post. Modern view here

Gomer moves to Liverpool

Ten years later, in 1871, Gomer had moved to Liverpool and has gained employment as a book-keeper. He may not have been in Liverpool long by this point as he is one of 9 lodgers at 36 Great George Street (now demolished). He was staying in a house run by John William Harrison, a watchmaker from Kent. His parents were still living in Pant, Abergele, his father is an agricultural labourer and his birthplace is listed as Cilcain, Flintshire.

Marriage and child

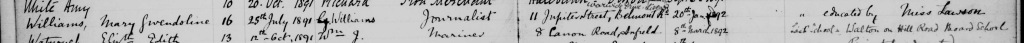

On 11th August 1874 Gomer married Liverpool-born Agnes Gilbert Watson at the United Presbyterian Church on Derby Road. Agnes’ parents were Scottish, her father was a rigger and her mother was a linen draper. As he was a draper himself, Gomer probably met Agnes through her mother’s business. On 25th July 1875 their daughter Mary Gwendoline Williams was born. At this time they had just moved in to 267 Fountains Road, Kirkdale (also demolished).

Death of his wife after just two years of marriage

Tragically, Agnes died aged just 32 on January 4th 1878. This left Gomer with the unenviable task of looking after his two and a half year old daughter whilst trying to maintain his job. Later census records suggest Gomer was short of money making paying for a babysitter out of the question. Thankfully his recently widowed mother and his sister-in-law agreed to move in to help him out.

In 1881 Gomer was living at 110 Herschell Street, Everton. He is listed as a widowed ‘Cashier & Bookkeeper’ in a cabinet maker and upholstery firm. His mother is living with him. His sister-in-law Annie Watson is looking after the house and his daughter Mary who has started school.

Money problems

Gomer moved residence at least five times in the 1880s. The terraced houses he lived in would have been brand new at the time, part of the massive house construction boom of that period. Fellow Welshmen played a significant part in the construction of Liverpool’s new housing.

From starting off in Herschell Street in 1881, he was listed in the transactions of Liverpool Welsh National Society as living at 37 Aubrey Street from 1885 to 1887. By 1888 he had moved to 37 Chirkdale Street (demolished). In 1889 he moved briefly to the Wirral, living at 6 Winstanley Road, New Ferry. The transaction of 1890 shows him living at 11 Jupiter Street.

Moving home so many times, in a short period, may indicate Gomer was in financial difficulty.

Gomer had started writing in this period. He had even started a newspaper called the Jester. This failed in 1883 (see later in this post) and must have drained his resources, and likely left him in debt. No record of bankruptcy appears in the London Gazette so we know he was able to pay his creditors. But Gomer’s modest income had to cover rent, and support three other people; his elderly mother (until 1883), Anne and his young daughter.

Listed as an Author on the 1891 census

Between 1881 and 1891, marks the start of his writing career, as the 1891 census shows him as an author. He was living at 11 Jupiter Street, Everton (also demolished). His mother Mary does not appear, it’s likely she died in Liverpool in 1883, aged almost 80.

Gomer is listed as married with Anne as his wife, but there appears to be no record of him marrying again. The record matches Annie – his sister-in-law. Perhaps they lived together as husband and wife? Mary was now 13 and she had been cared for by Anne for most of her life, likely viewing Anne as a mother.

Before the 1901 census, Gomer had moved to 9 Church Road West, Walton. Unfortunately, no mention of his writing career is given, instead he is a counting house manager in a drapers. Again Anne is shown as his wife.

By the 1911 census Gomer had moved to his final home at 3 Redvers Drive, Orrel Park.

The only clue to his writing ability is his occupation as an advertising manager at the Peter Walkers & Sons brewery.

We return to Gomer’s life story in the section Life after the book.

What we can gather from the census records

The census, taken every ten years since 1841, is the primary source of information for any researcher. Invaluable as they are, they only show the bare facts of a person’s life (or more accurately, the facts the person chose to tell the enumerator).

In the case of Gomer Williams, the census records give very little insight into the man’s literary career. From the census records alone, it appears that his career as an author did not last very long, because in 1901 he is just a ‘counting house manager’ at a drapers. This could not be further from the truth, because the years between the Census’ of 1881 and 1901 would be his most productive years as a writer, including his major achievement, his book.

However, the census records do indicate that his literary achievements did not give him any financial stability, and that he had to supplement it with regular work. This was not uncommon for Liverpool historians, Robert Griffiths ran a print and stationery shop on Aigburth Road, and James Stonehouse was Chief Superintendent of the Liverpool Markets.

Gomer begins his writing career

In contrast to the census records, the old newspapers held by the British Newspaper Archive and the National Library of Wales give us a wealth of information.

Gomer the Jester, a venture that lands him in court

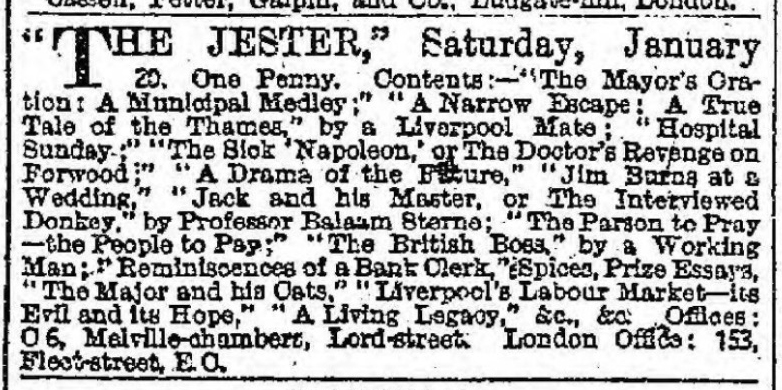

On the 23rd December 1882, Gomer started a new and exciting enterprise. He became the writer, editor, proprietor and publisher of a weekly penny-paper called the Jester. He had a small office at Melville Chambers, 50 Lord-street (now the site of Barclays bank). This was a satirical magazine that, as well as having humourous sketches, it appears to have had a strong Socialist viewpoint. It included articles such as The British Working Man, by his Boss and in the same issue The British Boss, by a Working Man and also Liverpool’s Labour Market – Its Evils and its Hopes.

Unfortunately, within four months Gomer’s ‘wit and satire’ had got him deep trouble. He was embroiled in a libel case held at the Police Court with Mr. Raffles presiding.

Gomer had published a defamatory article about an un-named company (but obvious to everyone as being Watts & Co. in Compton House, Church Street). Gomer was formerly a clerk at O’Neils, a carpet manufacturer directly opposite Watts & Co, and supposedly had inside information on their alleged anti-Irish recruiting policy.

The article was entitled ‘Boycotting Irish Assistants’ and claimed that all their Irish assistants were to be discharged. This claim was refuted by the owner who claimed ‘there were 92 Irish assistants in the service of the firm, and 24 of these were engaged during the past year’.

Sour grapes?

It appears that the Jester had appoached Watts & Co. several times to place advertisements in the paper ‘by a man who was chiefly remarkable for the redness of his nose’, But the requests were refused. Therefore, it’s possible that Gomer may have published the article out of spite.

Evidence incriminating Gomer

To prove that Gomer did not only act as editor, the original copy for the article was an exhibit in court and it was proven to have been in Gomer’s handwriting. He was forced to make an apology through his solicitor Mr Madden. Because he apologized, he avoided the case going to trial with a jury, so he only had to pay the costs. With no reserve capital, the publication ceased after 5 or 6 issues.

Gomer the column writer and romantic fiction author

Gomer also worked for several newspapers (apparently in a freelance capacity) including the Liverpool Mercury and ‘Commercial World’. He was also writing for the Liverpool Weekly Courier and the Cardiff Times in this period.

The Weekly Courier had a regular column called ‘Welsh Notes – by a Cambrian’ that was almost certainly written by Gomer. He also wrote for Y Cymro under the Arthurian alias Drem ab Dremhidydd.

Among the other column-writers who became authors was the Runcorn-born and Liverpool-raised author (Sir Thomas) Hall Caine. He and Gomer became life-long friends. Hall Caine had also set up the Notes and Queries Society in 1878. Through Hall Caine, Gomer became acquainted with its other members. Hall Caine (he never used Thomas, even after his knighthood) shared the same publisher. William Ralph Hall Caine, his brother, wrote an obituary to Gomer in 1916 (see below).

Gomer (writing in Welsh), once recalled an evening spent with Hall Caine and Welsh astronomer Isaac Roberts on 22nd February 1894. This was repeated in Y Brython after his death. It was probably at the home of William Edward Tirebuck who lived at 355 Park Road, close to the Ancient Chapel of Toxteth:

‘…a lovely evening when we sat in a house in Toxteth Park, at the same table as Mr. Isaac Roberts, Mr. Hall Caine, and Mr. Wm. Tirebuck’.

Translated from Welsh. Y Brython, 4th January 1917. National Library of Wales, Newspapers

Y Brython observed that Gomer’s friends included:-

an astronomer and two novelists and the three were members of the old Notes and Queries Society, and have made their mark in the world. Tirebuck has touched on Welshness in his Sweetheart Gwen, and we may soon see a Welsh text being treated with power, tenacity, and Celtic sympathy by Mr. Hall Caine.

Translated from Welsh. Y Brython, 4th January 1917. National Library of Wales, Newspapers

As we can see above, Gomer never forgot his Welsh roots. He would often return, fishing at Lake Vyrnwy with the Hall Caine family. From 1885 to 1892, his name appears as a member of the Liverpool Welsh National Society, who held their meetings in the Royal Institution in Colquitt Street. Before 1895 he wrote Llewelyn ap Iorwerth; An Historical Romance (based on the story of Llewelyn the Great).

In the 1890s, Gomer wrote news articles for a publication called Tailor & Cutter. No doubt his experience working in a drapers made him the ideal candidate (see also The Book section further down).

Also in this period he wrote another romance Davy’s Girl’s Revenge. In 1895 the Cardiff Times and South Wales Weekly News serialized another Welsh-themed story Blodwen Rees; a Story of the Cursing Well. This was accompanied by illustrations.

Blodwen Rees was advertised as ‘One of the best special Christmas numbers ever published in Wales’. The story was heavily publicized, the South Wales Gazette claimed it was by a local writer (apart from the fact he was from North Wales and lived in Liverpool):

…dealing with Welsh life and manners, superstitions, and religious beliefs. The scene of the story is laid in South Wales, and the plot is strong in love and jealousy.

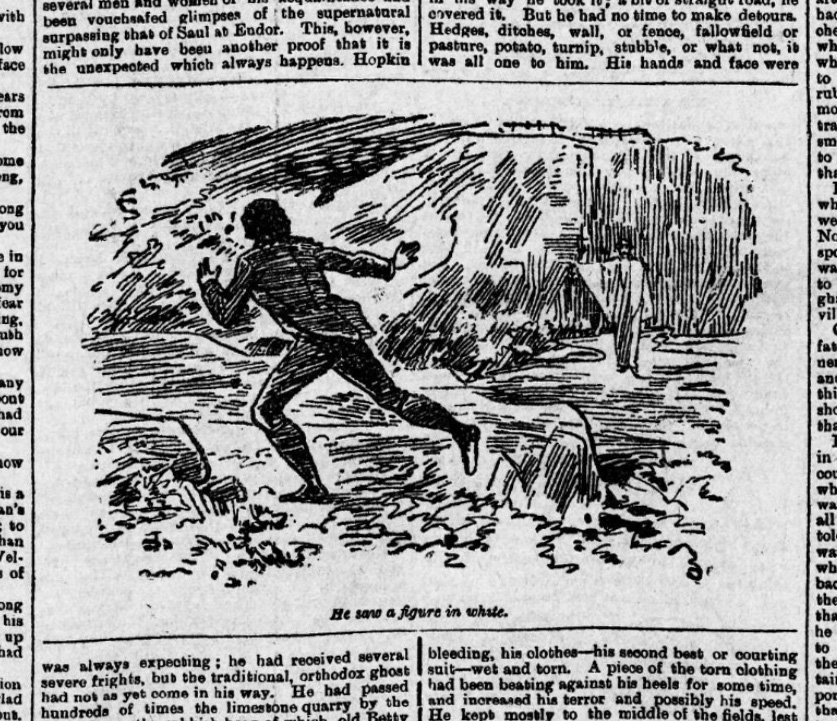

Chapter III ‘The Agony of Jealousy’ gives a flavour of the piece. It’s fair to say it’s more of a Mills & Boon than an academic work! This chapter deals mostly with Blodwen and her gentleman-caller Hopkin Thomas, wondering how long they can hold off their passion until her disapproving father Caleb Rees ‘a deacon and a rigid Dissenting farmer’ dies:

She was lying in his arms, her head thrown back, and a mass of glossy black hair falling like a curtain against the high back of the settie. Her cheeks were crimson, and a strange light shot from her big brown eyes. The devil had been very near the lovers to-night, and both had felt his hot breath on their souls. Beaten back for a time, be might return with double power. Blodwen feared he would. She would give Hopkin the bitters now. Do you think it will be long before we are married, Hopkin?” she asked…

…She watched his face keenly. Hopkin’s conscience rang “No” in his ears as loud as a trumpet blast, but all that came from his lips was a passionate kiss, which took the girl’s breath away “Hopkin.” she panted, you must not come so often. You must not see me again for a long, long time.

“Not see you so often not for a long, long time,” he repeated, slowly. What do you mean, cariad ? He relaxed his hold, and brought her face in line with the flickering fire-light, watching for her reply as a man might watch for an enemy coming upon him out of the darkness. The fear that some day she would grow weary of waiting, that she would throw him over before her youth led quite away was always at his heart, and now rose to his face. I mean that I cannot go on in this way any longer. Mother says people are talking about us—and—and I dreamt last night that we had been separated for ever, as a punishment for our sins!”

…The devil is in the girl to-night,” he thought. Perhaps it was. Something impelled her to tease him. Spooning, week after week, was very well, but why should he, who apparently made no great effort to hasten the happy day – who was simply waiting on “Providence”, in the shape of bis father’s death, to bask secure in the coming sunshine of her love..

Blodwen Rees; a Story of the Cursing Well. Gomer Williams.

Chapter IV on the same page ends with Hopkins running through turnip fields in terror after seeing a ghost of the Squire!

As a protection against ghosts he had once taken the stable lantern with him, but it only made the darkness more frightful. A thousand phantoms seemed to dance around him.

If you can bear it, more of Gomer William’s romantic drivel fiction can be read in the Cardiff Times, 1896

Gomer’s childhood inspiration for the stories

The first clue to Gomer’s influence for Welsh historical romances may lie in the name his parents chose for him. The Christian name Gomer became popular, predominantly in Wales, in the first half of the 19th century. William Camden had proposed a (now discredited) theory that Welsh people were descended from Gomer son of Japeph. The Welsh Baptist minister and writer Joseph Harris (1773 – 1825) had chosen the biblical Gomer as his bardic name. In 1818 Harris launched the weekly Welsh-language paper Seren Gomer (Star of Gomer). In 1823 the paper called on all people in Wales to choose a Welsh name for their children, over the increasingly common use of English names.

Born on an Iron Age hill fort

If we return to Gomer’s birthplace and family home, Garth-gogof in Abergele, it is no wonder why Gomer had such an interest in history and the romance of his Welsh homeland. The Williams’ house is huddled at the base of the huge, stone walled hill fort Pen-y-corddyn-mawr. The houses appear to survive today and can be see on the right of this photograph.

Gomer may have pretended he was from a local writer from South Wales when he wrote for the Cardiff Times, but his stories never strayed far from his childhood.

Llywelyn the Great

The area is overlooked by Gwrych Castle. This was built between 1810 and 1825 by the Lloyds (Llwydiaid) who shared ancestry with Llywelyn the Great – the subject of his historical romance Llewelyn ap Iorwerth.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic it temporarily became the location for I’m a Celebrity Get me Out of Here (usually located in Australia).

Gomer’s ‘Cursing well’

About six miles from the family home is the Holy Well (Ffynnon) of Saint Elian. Originally the water from this well was supposed to have healing properties but took on a more sinister reputation in the second half of the 18th century:-

But by the end of the eighteenth century the well briefly acquired a more sinister reputation for the power to curse and even to kill.

Llanelian-yn-Rhos, cistercianway.wales

Here we find the ‘Cursing Well’ of Gomer’s story. According to this clipping (almost certainly written by Gomer himself), even Liverpool people bought curses from the “priest” – “an old (Scottish) tailor.” Maybe Gomer used one of his old employers at the draper shop as the inspiration for the notorious Jack Ffynon Elian?

1897 – a very busy year

The same year his major work was published, he wrote an 11 part serial for the Liverpool Weekly Courier with the spicy title of Female Masqueraders; Or, Women who have passed as men. One begins with the even spicier introduction of ‘A romantic Will case and a female bridegroom’.

In the same year he was churning out romantic fiction, he wrote (anonymously) a series of serious (but sometimes humourus) articles for peer-reviewed medical journal Lancet called “Historical notes on medicine, surgery and quackery”.

It was at the very end of that same year that Gomer would finish his major work “History of the Liverpool privateers and letters of Marque with an account of the Liverpool slave trade”.

The book

Gomer’s major work (and only printed book) was published by Edward Howell of Church Street, Liverpool and William Heinmann of London. It was realeased in the last few days of 1897. It is ‘Affectionately inscribed to Hall Cain by his friend, the author.’ This was Sir Thomas Hall Caine mentioned earlier.

The book was in a very advanced state a year before it was finally published. The preface informs us that publication was held up because of the time taken ‘sifting of much curious original matter’. On 19th December 1896 a preview appeared in the Army and Navy Gazette. Another appeared in Tailor & Cutter on New Years Eve. The latter informs us that Gomer was a frequent contributor to their pages – because he was ‘intimately connected to the tailoring trade’.

The publication had a section relating to tailoring news across the country. Gomer’s contribution was writing the articles, this was anonymous but related specifically to Liverpool (but possibly all of them). In amongst news about shops opening or expanding and innovations in the trade we find that the history of Liverpool is never too far away from his thoughts. In between a story about Messrs. Taylor & Co. opening a shop in Islington, and ‘A new line in Leggee Twist’, he managers to cram in a story about ‘the Old Stager’ James Aspinwall (incidentally from a family of Liverpool slave merchants):

In January 1897, Gomer wrote to William Ewart Gladstone (Prime Minister 1892 – 1894. Died 19 May 1898). A prospectus of the book was sent through his publisher Edward Howell with a view of Gladstone granting permission to research some of the rare books and illustrations in his library. Gladstone (a subscriber to the book) agreed but he must have been nervous knowing that his father John was owned enslaved people on his plantations and even funded at least one slave ship venture:

The volume you announce, if you can really fulfil the title, will be of extreme interest, and I shall desire to possess it. With regard to the search and the inspection you purpose, you have only to name your day and hour, not later that next week, and the sooner the better, when on receiving notice I will take care that all shall be ready for you.

Liverpool Mercury – Tuesday 12 January 1897

The article also says that the subject has ‘hitherto been handled in a very gingerly manner’ and insures the new book will ‘deal with the facts as distinct from “whipping a dead horse”. To soften the blow, Gomer informs us in the preface that the slave merchants were worthy of regards as they were also ‘patriots and worthies of no common order’:-

He (writing in the third person) has directed his indignation against the system, or national sin, rather than against individuals, for many of the slave-merchants and slave-captains of old Liverpool claim our regard as patriots and worthies of no common order.

Self-promotion and self-penned reviews

Once the book was published, Gomer may have exploited his position at the Weekly Courier (who were in the process of publishing his Women who have passed as men) to promote it. In January 1898 a large two column review was published- no doubt Gomer supplied his own copy. The review (too long to show in its entirety) ends with ‘In conclusion it remains to be said that Mr. Gomer Williams has rendered a great service’.

This was not the first self-penned review to appear in the Weekly Courier. On the 8th January 1898, just days after publication (and the final installment of Women who have passed as men, two articles appeared on the same page but completely separate from each other. Here Gomer uses language now considered extremely racist but even then was derogatory, as the N-word appears nowhere in his book. Perhaps as a newsman, Gomer uses the vocabulary to appeal to a newspaper audience who were unlikely to purchase the book so instead presented snippets?

The words chosen (by Gomer) to describe John Newton is shocking:-

The Rev. John Newton, vicar of Olney, Cowper’s bosom friend, Cowper’s collaborator in the Olney hymns, rector of St. Mary Woolnoth, London, and humanitarian to the backbone, was in his pre-clerical days as stout a slave-skipper as ever kept “N—–s” under the hatches’.

It’s interesting to compare it to the less damatic (and not racist) preview that appeared in the Dublin Weekly Nation in January 1897:

With his experience as a journalist and magazine publisher, Gomer used several methods to promote his book in the press. Here he plugs his book, and at the same time suggests Spain should bring back Privateering to revenge her lost fleet in the Anglo-Spanish war (1896-1908).

Reception of the book

The Evening Mail ran a mixed review on the 8th December 1897. It stated (somewhat sarcastically) that ‘A very interesting and instructive book might be written some day, on the history of privateering and privateers’, but Gomer’s book was ‘more of a chronicle that a history’ and had ‘little regard to literacy and hardly any attempt at historical analysis’.

These sentiments were shared by the Army and Navy Gazette on the 26th February 1898. But at least they ended their review by saying ‘We closed Mr. Williams with regret’:-

We greatly regret that Mr. Williams has not been more of an historian and less of a mere chronicler, though we confess many of his narratives abound with interest.

Army and Navy Gazette – Saturday 26 February 1898

On 8th January 1898, the Liverpool Weekly Mail (previously mentioned as probably self-penned) wrote that, in regards to the history of Liverpool and the slave trade:-

In conclusion it remains to be said that Mr. Gomer Williams has rendered a great service.

The London Evening Standard included it in their ‘Some new books’ column in March 1898. In regard to the slave trade chapters, it stated:-

pessimists should study this volume, for in this direction, at least, we have certainly improved on the good old days.

In March 1898 an extensive 17 page review of the book appeared in the Welsh-language paper Y Traethodydd by the Welsh-born, Liverpool writer Eleazar Roberts.

Ramsey Muir in his 1907 History of Liverpool called the book:

an invaluable collection, in chronological order, of materials drawn from newspapers, the private papers of various firms, etc., and it sheds much new light upon its subject.

Searching the British Newspaper Archive, it appears little mention is made of the book very soon after publication – and until well into the 20th century. By that time, Gomer’s book was used extensively by researchers and still is today. While most of the book covers privateering, the smaller slave trade section has received the most attention.

Later criticisms

Although Gomer’s research is often cited by historians, some of his statements and figures were later challenged, including the profits the investors in slave ships made:-

…no aspect of slavery has been so clouded by the obscurantism of the traders and the exaggerations of anti-slavery writers as the question of profitability. Perhaps the most misleading of all “authorities” was Gomer Williams (1897), who confidently described “profits” of between 100 and 300 percent simply by deducting the cost of trade goods from the gross returns on the sale of slaves in the plantations without accounting for any overheads. Some of Gomer Williams’ figures even find their way into his illustrious namesake’s Capitalism and Slavery, though Eric Williams and most of his imitators generally give more credence to the figure of 30 percent profit more carefully calculated by J. Wallace of Liverpool in 1797. Wallace’s figures, however, derive from the years 1783 to 1793, a period of peace and prosperity; and Eric Williams himself cites Clarkson’s statements that over the period of the American and maritime war, Liverpool slave traders actually lost £700,000, and the London merchants declined to engage in slave trading between 1763 and 1778 because of its unprofitability.

Sinews of empire : a short history of British slavery. Michael Craton, 1974

Criticism (sometimes unfounded) has also been directed to Gomer over his narrative of Liverpool’s eventual dominance over Bristol. C. M. Macinnes writing in 1939 (in a bid to claim the reason was not Liverpool’s business accumen, but Bristol merchants who diverted into owning plantations) went as far as accusing Gomer of being ‘a strong champion of of Liverpool’ and his theory a ‘smug assumption’ of ‘local patriotism’. rather than scholarship.

It has to be said that smug patriotism is a strange choice of words to describe a Welshman denouncing his adopted town’s involvement in the slave trade!

Indeed, the smug assumption of superior economic efficiency on the part of Liverpool testifies more to the local patriotism of Gomer Williams than to his historical erudition.

A Gateway Of Empire, C. M. Macinnes. 1939

If anything, Macinnes appears to have had misplaced patriotism towards Bristol, by claiming that Bristol was overtaken by Liverpool through choice.

Gomer’s description on London’s role has also been questioned:-

Historians’ misunderstanding of London’s role apparently dates from 1897, when Gomer Williams, an influential historian of the Liverpool slave trade, described how Liverpool became “the chief slaving town of the Old World” in the eighteenth century…

Though Williams failed to document his assertion, he had obviously done a great deal of research in preparing his book, and historians to the present time have depended heavily on him. In his assessment of the role of London in the eighteenth-century slave trade, he fixed a stereotype which survived his work for at least seven decades.

London, metropolis of the slave trade, James A. Rawley, 2003

In 1976, F. E. Sanderson (apparently worried about the naming of some of Liverpool’s most prestigious merchants being involved in slavery) referred to the book as:-

Gomer Williams’ somewhat muck-raking history of the Liverpool slave trade

The Liverpool Abolitionists. F. E. Sanderson, 1976, THSLC

Life after the book

To return to the 1901 census, just three years after the book, Gomer is living at with Ann (listed as his wife) and his daughter at Church Road West, West Derby. He is a Counting House Manager at a drapers.

By 1911, Gomer had switched to a career in advertising which can be seen by his occupation, an advertising manager at a Brewery (Peter Walkers & Sons).

Gomer and Anne were not home on the day of the census, instead are visitors at the house of Agnes Lyle Boyle who lived at 15 Sefton Road, Liscard. Agnes had given her occupation as suffragette. This was a much safer option than what the ‘Votes for Women’ campaign had proposed – boycotting the census altogether and risking a £5 fine or a month’s imprisonment.

Brewery advertising

The following advertisements are likely to be examples of Gomer’s copy-writing skills, as they date from the same period:-

Gomer’s home at this period was 3 Redvers Drive, Orrel Park. Gomer’s daughter, Mary Gwendoline, had married in 1907 but her new family were living at the same house. Her husband John Morison is listed in 1911 with their 3 year old son Allan Duncan.

Death of Gomer

Gomer Williams died on 22nd December 1916 and was buried at Anfield Cemetery. Mary Gwendoline Morison was present at the time of his death at 3 Redvers Drive. Gomer had been in ill-health and suffered from heart as the cause of death was ‘Morbus Cordis. Some years’.

Sadly, the notice of his funeral in the Liverpool Echo gave no mention his writing career. Instead it relates only to his advertising job at the brewery :

WILLIAMS, Dec 22nd, 3 Redvers Dr, Orrell Park, Gomer WILLIAMS [late of Peter WALKER and Sons 105 Duke St] interment at Anfield Cemetery tomorrow.

Liverpool Echo, 29 December 1916. care of old-merseytimes.co.uk

Gomer was buried in an unconsecrated section with his in-laws Harris Watson and her husband George Braidwood. His wife Agnes was not laid to rest in the same plot, neither was Anne his sister-in-law. The fact he was buried with his in-laws may further indicate that he was never married to Anne.

In loving remembrance of George BRAIDWOOD,

who departed this life March 4.1878, aged 46 years.

“Until the day break,”

and the day star arise in our hearts.’

Also of Harris Watson, wife of the above,

who departed this life January 11.1890, aged 55 years.

“Patiently endured.”

Also of Gomer WILLIAMS,

brother-in-law of the above,

who died Dec. 22.1916, aged 69 years.23203 BRAIDWOOD, WILLIAMS. (G.2.1131)

Photograph by John Parry via billiongraves.com

Photograph: Daz, Bygone Liverpool

Buried in good company

Although his achievement is not shown, Gomer is in good company. The esteemed Liverpool artist and historian William Gawin Herdman, and also the historian of Toxteth Park, Robert Griffiths, are buried in the same cemetery. Fellow Welsh-born Liverpool writer Eleazar Roberts (who wrote the 17 page review of Gomer’s book) is also buried there.

Obituary to Gomer

His obituary ran in the Liverpool Daily Post on December 29th. This was written by his old newspaper colleague William Ralph Hall Caine (brother of Sir Hall Caine who Gomer inscribed his book to).

Hall Caine’s fond obituary finally gave credit to his friend skills as a writer and a historian. It can also be seen from this that Gomer was planning to publish his 1897 serialized newspaper work Female Masqueraders; Or, Women who have passed as men in book form. Sadly this would never materialize.

As it is the source of much of this research, it is reproduced in full below.

THE LATE MR. GOMER WILLIAMS.

APPRECIATION OF A LIVERPOOL HISTORIAN.

By W. RALPH HALL CAINE.Permit me to explain for the benefit the younger generation of readers that the intellectual life of Liverpool has suffered loss. Mr. Gomer Williams had the luck to carve a niche for himself in the history of the Mersey port, by his splendid volume entitled “The Liverpool Privateers.” In the preparation of this work the author had a small mountain of old papers, logbooks, ships’ charters. &c.. placed at his disposal —enough material, in fact, to dwarf the soul of any less conscientious and industrious historian. And though time, dust and worms of a century had defaced these records of stirring drama by land and sea, in Mr. Williams’s hands they were made to yield up their story. Nothing was left be desired on the score of accuracy, completeness, and vigour in the telling. Therein “Mind your eye Crowe” and many another celebrity of the Slave Trade have been assured immortality.

The reception accorded to “The Liverpool Privateers” generation ago by the Press of Liverpool and Manchester, and not least remarkable, the large amount of space given to the volume by the leading reviewers of London, would have justified most authors, in like happy circumstance, to stalk forth with air assured pride and dignity. In the case of Mr. Gomer Williams these small, foolish, amusing, but pardonable graces of mein were remarkable only for their complete absence. I never knew any man to whom the immaterial rewards, the so-called embroideries of authorship, were of less concern.

The distinguishing note of his character was a genius for taking pains and then, singularly enough, leaving the result to take care of itself. The last important task which he devoted his industry was a work held up by the war. It tentatively called “The Masqueraders,” and consists of an enormous body of material—enough to set up twenty novelists with plots for the period of their lives. It an intimate and particular account of exciting adventure, of women who have, for period of years, masqueraded as men in the Army, Navy, Church, diplomacy, business, private life; together with the even more remarkable careers of men who have successfully passed themselves off women, marrying and all the rest of the apparently ridiculous and impossible nonsense. When the present conflict of nations has subsided, I doubt not, that, many readers will gladly turn for interest and excitement this record of amazing fact and gratefully yield their homage to the author who has now passed hence.

In his earlier years Mr. Gomer Williams was engaged in commerce, but the odour of printers’ ink had imposed its charm, and to writing for the Press he devoted the larger half of his life. He wrote a Welsh novel in the vernacular, called “Llywelyn lorwerth.”

For a period he edited a Liverpool weekly miscellany which, at, its projection, was to be called “Dicky Sam,’ but the journal destined never appear under this name, as a rival publisher anticipated the appearance of the newcomer registering the distinctive title immediately the secret was disclosed publicity of the hoardings.

Mr. Gomer Williams was a true Celt, as that term is understood in connection with the Brythonic branch the race, in height, colour, shape of head, character of mind.

Twenty-five years ago, he was a frequent contributor to the Liverpool Mercury, instructing questions affecting his compatriots, from politics and religion to beautiful and fragrant aspects of an incomparable folklore, thereby helping the mere Saxon understand that of which birth had denied him knowledge. And, curiously enough, the last words ever penned wore written me, week ago, bearing on the Celt’s dream of Heaven, that mysterious land everlasting youth lying across stretch of water the West, where the Sun reposes at full of day and there is no night.

Of late years Mr. Gomer Williams was associated with Messrs. Peter Walker and Sons, the well known brewers, and their Duke-street office had charge of a department concerned with printing, advertising, and other details to which his experience gave him special aptitude.

He was an enthusiastic angler, and I recall, with a thrill of gladness, many happy hours with him, in far-off years, on the banks of some gently-flowing tributary his beloved Vyrnwy.

Liverpool Daily Post – Friday 29 December 1916. British Newspaper Archive

Another obituary appeared in Welsh in Y Brython (4th January 1917, pg.5 – 6). This gave a visual description of him:

a man of smart appearance with a fleece of curled black hair.

See also the section Gomer’s descendants at the end of this post.

A comparison of Dicky Sam and Gomer Williams leads to an interesting theory

As mentioned in the introduction, an earlier work was published in 1884 entitled Liverpool and Slavery: An Historical Account of the Liverpool-African Slave Trade was written by an unkown author under the pseudonym ‘A genuine Dicky Sam’. This was a phrase to describe people from Liverpool long before ‘Scouser’ appeared.

Origin of the nickname Dicky Sam

The origin of the appellation ‘Dicky Sam’ has been debated as early as 1847 (Liverpool Mercury – Friday 28 May) – 27 years after the first evidence of it in print.

Gomer provides an often-repeated but highly unlikely explanation (almost certainly borrowed from the Cockneys) of being ‘born within the sound of St. Nicholas’ bell’. The plausibility of this must be questioned as the locality of the church next to the river Mersey would also include residents of Birkenhead! Another incorrect theory is that it was named after Richard Samuels who had a pub on Mann Island. No such man existed and the pub came after the nickname, not vice versa.

By far the most likely origin is a contemporary explanation for the name given by James Aspinall (1795 – 1861). The explanation is the same given in 1847. It appears that in the 18th century, just as today, every Liverpudlian’s name was abbreviated by his friends – even if you were the most important merchant in town.

Aspinall would have heard the term used many times as a child in the late 18th century before it appeared in print in the early 19th. This led to Liverpool being known as a ‘town of Dicky Sams’. This is reminiscent of ‘Tom, Dick and Harry’ that appeared circa 1657, although the Liverpool version is used in a genial sense rather than applying to a group of unknown individuals.

And we had also our circle of wits, whose sharp sayings were passed round, as household words, from mouth to mouth, and so afforded pleasure and amusement, as they spread from set to set, from one extremity of society to the other. First and foremost in this bright and brilliant band, we must place Mr. Silvester Richmond, or “Sil Richmond,” as he was generally called. Next to him was Joe Daltera. And with them we must join Sam Pole, and “Jim Gregson,” who lived in Rodney-street, a man of racy humour, with a fund of originality about him which revelled in the utterance of good things. And here be it observed, that, as Liverpool is still called the town of “Dicky Sams,” so, in those ancient days, its people were all Sils, and Joes, and Sams, and Jims. It was the custom of the place, and equally observable in every rank of society.

Liverpool a few years since, James Aspinall, 1852

Dicky Sam the author

The true identity of the writer of Liverpool and Slavery has never been established. It is not surprising that the author chose not to reveal their name, although Liverpool’s involvement with the African slave trade had been over for decades, there were still merchants alive that had made their wealth from it, so too were some of the children of the 18th and early 19th century merchants. And these were often the most powerful men in the city (the future Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone to name just one).

The very first paragraph of the book is actually an apology for bringing public attention to those merchant. Although he then assures his readers that ‘Nothing personal of any kind is intended to the individuals’.

He also claims (probably correctly) that if the current readers who ‘point the finger of scorn’ had lived in that period, they too would have ‘gladly been partakers in the gold it brought’.

A red herring

The only clue to Dicky Sam’s identity is the beginning of the first chapter where he informs us ‘I have until recently, lived for a long period in Red Cross Street and Moor Street’. We may not put much trust in the statement as it was not uncommon for authors of historical books to not only assume a nom de plume, but also a fake back story. This was the case with another famous history of Liverpool Recollections of Old Liverpool; by a Nonagenarian (1863). This was supposedly written by a Liverpool-born man in his 90s who could recall Liverpool in the previous century – but was later revealed to have been the work of 54 year old James Stonehouse (born in Wandsworth, Surrey who didn’t come to Liverpool until 1833!)

The first chapter begins with using what is now seen as the most racist word possible to describe the very victims of the book. The use of this word may possibly be excused by it being published back in 1884. But according to The Imperial dictionary, on the basis of Webster’s English dictionary of 1883 it is used in ‘depreciation” (reducing value) ‘or derision’ (contemptuous ridicule or mockery).

But perhaps the author is using that derogatory word for effect? To make a contrast with the contemporary (free) ‘negroes’ that passed him on Mann Island earlier in the same sentence. Afterwards he only uses the N-word within quoted (but invented) dialogue, elsewhere the author uses ‘negro’.

A challenge from Dicky Sam to discover his identity

The author anticipated the trouble he may have stirred up by naming the Liverpool merchants families with links to the slave trade. In stressing that he is an ‘every day common place being’ he appears to be insisting his motives were not political. In doing so he almost challenges his readers to discover his true identity:-

When I appear in print, if I should have the audacity to do so, some may be trying to find out who I am. However, I may say, to satisfy all concerned, that I am an every day common-place being, with a strong mental predilection for things not generally known.

Adam Bowker’s ‘Old Curiosity Shop’

Liverpool and Slavery was published by Adam Bowker and Son of 27 Renshaw Street. The small print-run of just 500 copies was printed by A. Russell, Son & Bailey at 30 Moorfields.

Bowker was born in Manchester in 1811 but came to Liverpool in 1841 with his family. He appears on the census as a ‘traveller’ living in Scotland Road. Ten years later he appeared as a stationer living in a court off Clayton Street. By 1861 he had opened a book and curio shop at 17 Stanley Street. He had moved to Renshaw Street before 1881. His ‘Old Curiosity Shop’ supplied Liverpool historians with many rare maps old maps, directories, old newspapers, coins and old military medals. He had a passion for anything relating specifically to the history of Liverpool, this made his shop a vital source for anyone researcher.

Bowker (patronised by the Prince of Wales, no less) published several books, illustrations and maps including:-

(M’Gahey’s) ‘Views of Dale Street in 1850’

(Leland’s) ‘Historical Map of Lyrpole, from a very curious plan’,

(James Boardman’s) ‘Liverpool Table Talk a Hundred Years Ago’ (1871)

(Adam Bowker) ‘Funeral records of Liverpool Celebrities’ (1876)

He died in 1883 so Liverpool and Slavery must have been published by his son Edward.

A comparison of the two books

As they deal with the same subject matter, Liverpool and Slavery and the slavery chapters of Gomer’s book understandably have a lot in common. Both end with lists of merchants trading to Africa and tables of shipping – although Gomer went much further in his research.

One major similarity to the two works, is the prominent inclusion of the Isle of Man slaver Captain Hugh (mind your eye) Crow. Dicky Sam devotes several pages to Captain Crow in chapter XII. Gomer devotes the entire last chapter to him.

When Gomer’s included Crow, it was much to the delight of his friend ‘the Manx novelist’ Hall Caine who moved from Liverpool to the Isle of Man and often wrote about it. Hall Caine’s brother William Ralph wrote what is ‘Considered by many to be the worst book on the Isle of Man ever written’. He mentions Crow’s appearance in Gomer’s book in the chapter ‘and thence to Ramsey’. He also mentioned Hugh Crow in his obituary to Gomer.

Crowville is linked with the memory, not always of the tenderest, of Hugh, known throughout the West Indies aforetimes as ` Cap’n Crow,’ or ‘ Mind your Eye Cap’n.’ Our island and its near waters were not spacious enough for so daring an adventurer.

The exploits of the adventurous old seadog are recounted in the vivid, stirring pages of Mr. Gomer Williams, in a volume entitled ` The Liverpool Privateers,’ a veritable storehouse of inspiration for the writer of boys’ stories.

Isle of Man, W. R. Hall Caine, 1909

As stated earlier, Gomer shared the same publisher as Sir Hall Caine (Heinemann). He must have winced when he read his friends description of slave auctions in Liverpool held at the Goree Piazzas. The first were only half-erected by 1802 and destroyed by fire shortly after, making this story impossible, and an early example of the popular myth (although auctions of enslaved people quite possibly took place on the Goree Causeway the warehouses were built on):

Shall I confess to you that in the bad days of the English slave trade the four merchantmen that brought the largest black cargo to the big human auction mart at the Goree Piazza at Liverpool were commanded by four Manxmen!

The little Manx Nation, Sir Hall Caine, Published by William Heinemann – 1891

Some of Dicky Sam’s passages appear to be works of imagination. This is unfortunate but understandable, without the wealth of archives that modern researchers have, and without even leaving their home.

In 1941 Arthur C. Wardle (who was often writing letters to the local press dismissing local myths about the slave trade) referred to Dicky Sam’s book as ‘a rather imaginative booklet’. (In a review of Averil Mackenzie-Grieve’s book that had an illustration of ‘slaves being sold on the Liverpool quayside’ (incidentally, this was amended to African quayside when reprinted, see below).

Still, Liverpool and Slavery shown a determination to find original records (on the whole) to attempt a history of Liverpool’s involvement in the slave trade. F. E Sanderson commented on the accuracy of some of Dicky Sam’s material:

(Dicky Sam) claims to use official sources. It should be treated with some discretion: Henry Peet, the Liverpool historian, suggests that the author used copies of manuscripts for his sources and transcribed them inaccurately

Comment in the Peet Papers, Harold Cohen Library, Liverpool University.

These errors, and in some case even fabricated sections, never stray too far from the truth and the creative writing style helps to convey the horror of the trade. For the great majority of people since 1884, Dicky Sam’s book has served as an introduction to the subject.

Gomer too was not above adding a bit of theatre to convey the immorality of profiting from the slave trade. Gomer stated in his preface that he had ‘gained access to original sources of information never before tapped’ and where he has relied on a secondary source he has acknowledged the source:

The other and principal sources drawn upon are the files of old newspapers, magazines, and other contemporary records requiring no little patience and enthusiasm to ransack. In a few instances, where information on special points has been derived from other authors, as in Professor Laughton’s admirable account of Captain Fortunatus Wright, it is acknowledged either in the text or in a foot-note.

This isn’t actually true, in several cases he repeated, almost verbatim, information from Dicky Sam.

Repetition of errors reveal the sections Gomer copied from Dicky Sam, rather than finding original records

Before we cover the next section that deals with false information about the slave trade, we should make it clear that our intention is not to undermine the evidence of Liverpool’s massive involvement. As this section deals mostly with the public auctions of enslaved people in England, a comprehensive list of those that appeared in newspapers at the time can be found here. This is not complete and more are still being discovered. The same site has a database for advertisements place by owners of enslaved people who offered rewards when they ran away (put Liverpool in the search box). You can search for ‘Liverpool’ in the ‘Place Registered’ field of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade – Database to get 218 pages of results spanning only from 1711 to 1808 (not complete).

As both books cover the same subject, the information we can be sure Gomer copied directly from Dicky Sam are those that have no original source. As the were likely invented by the latter (but usually based on a real advertisement, or a combination of several). These include the following from Liverpool and Slavery:

Many curious advertisements have appeared in the old local newspapers. One, I recollect, ran as follows: –

A fine negro boy, to be sold by auction. He is 11 years of age; the auction will take place at the Merchants’ Coffee House, Old Church Yard. Sale to commence at 7 o’clock, by candle light. By order of Mr. Thomas Yates, who

hath imported him from Bonny. Auctioneer, James Parker. ; –Liverpool Chronicle.

Gomer repeats this advert but neglects to name the newspaper issue it appeared in, or that the coffee house in the Old Churchyard was called the Bath Coffee House at that time. Importantly he doesn’t even credit Dicky Sam:

In the short-lived Liverpool Chronicle, James Parker, auctioneer, advertised for sale by the candle, at the Merchants’ Coffee-house, a fine negro boy, 11 years of age, imported from Bonny, by Mr. Thomas Yates, a Guinea merchant, who lived in Cleveland Square.

One error by Dicky Sam is certain; The Merchants’ Coffee House was located in Dale Street in this period and not Old Churchyard (only there from 1773). Gomer may have been unsure of this in 1897 because he omitted the location, instead he stated elsewhere it was erected ‘about the middle of the eighteenth century’. This proves that the advertisement was not entirely authentic.

Picton, Gomer Williams, and other writers are clearly wrong in saying as they do that the Merchants’ Coffee House in Old Churchyard was erected about the middle of the eighteenth century, and nearly all the sales they allude to in connection with the Merchants’ Coffee House took place in Dale St.

The early coffee houses of Liverpool. A. H. Arkle, 1912, HSLC

Several researchers, including ourselves and the University of Glasgow’s Runaway Slaves in Britain project, have tried to source the original advertisement to no avail. Dicky Sam says he ‘recalled’ the advert, but as it was the Liverpool Chronicle it must have been 120 years earlier. Unless he recalled seeing it in an archive but transcribed it incorrectly? A similar (but less detailed) advertisement appeared in the Liverpool Chronicle in December 1768:

A Fine Negro Boy, of about 4 feet 5 inches high, of a sober, tractable* disposition, 11 or 12 Years of Age, talks English very well, and can dress hair in a tolerable way.

Liverpool Chronicle, 15 December 1768

Note: ‘Tractable’ is a word often used in these advertisements, a definition shows how sickening its use is:

*Tractable. (Adjective). Easily managed or controlled; docile; yielding: a tractable child; a tractable disposition.

Another example of not crediting material that can be proved was taken from Dicky Sam is the following:

Dicky Sam:

Here is a specimen of an auctioneer’s bill:-

Twelve pipes of raisin wine,

Two boxes of bottled cyder,

Six sacks of flour,

Three negro men,

Two negro women,

Two negro boys,

One negro girl.

Gomer Williams:

In an auctioneer’s bill of the period, we find, “twelve pipes of raisin wine, two boxes of bottled cyder, six sacks of flour, three negro men, two negro women, two negro boys, and one negro girl.

Both authors claim the wording came from an auctioneer’s handbill, yet if that artefact was in existence in the late 19th century, it certainly isn’t in the 21st. Far more likely it is another composite by Dicky Sam, here is a similar advertisement that Joseph Dahera (Daltera) placed in 1757:

Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser and Mercantile Register, 17 June 1757, p.4.

To be SOLD,

Ten Pipes of Rasin WINE, a Parcel of Bottled

CYDER, and a Negro BOY.

Apply to Mr. Joseph Dahera, Merchant, in Union Street.

Who sells, at his Warehouse near the Salthouse Dock gates,

FINE, SECOND, and COARSE FLOUR,

In Parcels, or by the single Sack, for the Convenience of private Families.

(Repeated 24th June; 1st , 8th 15th 22nd July; 5th, 12th August 1757).

Dicky Sam’s and Gomer’s versions are often repeated to this day, like here in an education pack for the International Slavery Museum, where it appears (incorrectly) with date of Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser, 1756. This was actually the next paragraph in Gomer’s book relating to the sale of the snow Molly.

More examples

These are just a few examples, but there are more. Gomer repeats Dicky Sam’s claim that enslaved people were ‘sold on the steps of the Custom House’.

Although it’s highly possible this happened (with the Custom House’s proximity to the Old Dock), it is likely to be a misinterpretation of advertisements from 1768 for ‘A handsome Negro boy from Angola’ in the Liverpool General Advertiser, or the Commercial Register. The sale took place at ‘the Sign of the Custom-House, in Brooks’s Square’. Stainton was a Cooper and this was a public house he ran that was next to the Custom House (not the public building itself).

You can read more about these on a Yo! Liverpool post by Daz, from 2015.

No mention of Dicky Sam in Gomer’s book

Gomer never acknowledged the sections he copied from Dicky Sam, even though he claimed every secondary source had an acknowledgement or footnote. Regarding errors made by previous historians Gomer assures us that:-

The utmost pains have been taken to ensure accuracy, and the reader will find the statements of more than one authority corrected.

He did however correct Baines on page 596 and Picton on page 173 and 619. Why did Dicky Sam remain unscathed throughout?

Gomer mentions the full term ‘A genuine Dicky Sam’ twice in his book – never referring to the book, but as turn of phrase. On one occasion he used it to describe ‘the Old Stager’ James Aspinall (referred to earlier who died in 1861).

Why would a Liverpool-based historian shamelessly copy the work by an earlier Liverpool author but give no credit, even though ‘all rights reserved’ was printed on the frontispiece of Liverpool and Slavery? Why didn’t correct the errors he knew Dicky Sam made?

The likeliest explanation is that Gomer Williams was the author of both books.

Was ‘Dicky Sam’ an alias for Gomer Williams?

Returning to Mai Roberts’ article from 2020, the author wonders whether the true identity of Dicky Sam was Gomer Williams. We also thought this is highly likely.

Ignoring the fact that they both deal with the same subject matter, Dicky Sam often uses what Wardle called a ‘rather imaginative’ writing style to get his point across. In Chapter II he speculates on the dialogue of a slave auction:

A voice in the crowd says “£5.” The auctioneer replies– “Why he is worth £50, and only £5 offered. Hold your Head up Cæser.”

…At the end of the sale the crowd breaks up, and slowly retrace their steps to their varied homes, filled with melancholy thoughts, to feel and know that a human being has been bought and sold.

Liverpool and Slavery, A genuine Dick Sam. 1884

But it is in Chapter VIII’s ‘Story of the murder on Nova Scotia’ where Dicky Sam really lets his historical fiction writing go wild. In a chapter devoid of historical accuracy, he mentions looking over some old manuscripts in his ‘grandfather’s secretaire’ where he came across the names of two ‘sturdy merchants’ he names Ralph Martin and Tom Norris.

Here he tells the story of the murder of George the son of Squire Starkey (a name worthy of Gomer’s Blodwen Rees romance) and how Will Derrick ended up on the slave ship Dart.

Messrs. Martin and Norris evinced great surprise; they had never known the true history of George Starkey, who was murdered in his father’s office. Mr. Derrick continued by saying, “several days after this event, I was walking by the Goree Piazzas, when I was met by two sailors ; after some conversation, we went into the Coffee House by the Church Yard. I remember drinking; I must have fallen asleep, but when I awoke, I found myself on board the slave ship ‘Dart,’ bound for Africa for slaves to the West Indies. She is owned by William James of Water Street, and I have been in the slave trade ever since, and such is my account of Squire Starkey’s fate, and the reason for my leaving you so suddenly.

Liverpool and Slavery, A genuine Dick Sam. 1884

Incidentally, William James invested in over 130 slaving voyages from the 1750s to 1770s. Once again, Dicky Sam made the same error about the Goree Piazza. James died in 1798 but construction of the Goree Piazzas was only less than half completed when it was destroyed by fire in 1802.

This writing style of Dicky Sam is very similar to the historical fiction that dominated most of Gomer’s writing career.

Gomer listed as an author in 1891 may provide a clue

We know that in 1891, whilst living at 11 Jupiter Street, Gomer had told the enumerator he was an author. But this is between the Jester failing in 1883 and his romantic fiction of the mid 1890s. The census was 8 years after the Jester and 7 years after Liverpool and Slavery was published. But (and it’s a big but) it was 6 years before Gomer’s privateer and slavery book. Could it be that Gomer had inadvertently revealed his secret alter-ego to the enumerator?

Not the best time for Gomer to use his own name

Liverpool and Slavery was published just one year after Gomer was found guilty for the article he wrote in the Jester, perhaps after being ridiculed in the press it wasn’t the best time to use his own name?

With a few exceptions, Liverpool and Slavery had a very modest but positive reception. There wasn’t the backlash the author probably expected in his home town.

Perhaps Gomer wished to return to the subject in much greater depth – but now with the courage and confidence to add his own name?

Gomer used the name Dicky Sam a year before the book was published

If we return to Gomer’s obituary by William Ralph Hall Caine, he wrote that Gomer’s publication the Jester was originally going to be called ‘Dicky Sam’ (a name also often used by people writing letters to newspapers – usually when complaining about the council).

Perhaps W. R. Hall Caine couldn’t resist the temptation to hint at his friends alter-ego by apparently dismissing it? Was this an in-joke to friends and family?

For a period he edited a Liverpool weekly miscellany which, at, its projection, was to be called “Dicky Sam” but the journal destined never appear under this name, as a rival publisher anticipated the appearance of the newcomer registering the distinctive title immediately the secret was disclosed publicity of the hoardings.

Advertisements placed by Gomer for his Jester publication under the earlier intended title of Dickey [sic] Sam can be found in the @BNArchive. They start from 18th December 1882 when he ran teasers in the local press.

In one Gomer quoted Macbeth; ‘Read Dickey Sam, and throw physic to the dogs‘.

Just four days later, Gomer placed the first of many ads where he was furious that the Porcupine used ‘a shabby trick’ to steal his idea:

It was not the only time Gomer used an alias

Gomer used at least two other aliases during his writing career, and quite possibly more when he was writing romantic fiction. Mai Roberts pointed out an obituary in the Y Brython on the 11th January 1917, this stated in 1895 he used the pseudonym Drem ab Dremhidydd (a name taken from Arthurian legend):

Hast thou heard what Dremhidydd sung,

An ancient watchman on the castle walls?

A refusal is better than a promise unperformed.

Thanks to Mai Roberts, we know that Gomer wrote using that alias (in Welsh) in an article about Daniel Owen’s final novel Gwen Tomos. Owens had died on the 22 October that year. The title of the ‘review’ is ‘Gwen Tomos dan Farn ym Mro Hyd a Lledrith’ (Gwen Tomos under judgment in the land of magic).

Here we have six good reasons to suspect Gomer as the author Liverpool and Slavery, and why he chose that alias:

1. He already used that name just a year before Liverpool and Slavery was published. He was so aggrieved at the Porcupine after they ‘stole’ that the advert above appears repeatedly from December 1882 through early 1883. (Liverpool and Slavery was published before October 1884).

2. He couldn’t use his own name because he was worried about possible consequences (see an example below).

3. Gomer couldn’t use his own name because was it connected to a recent libel case that had considerable press coverage.

4. Gomer’s own name was obviously Welsh. The whole premise of the book is that it was written by a local man. A local person criticizing Liverpool’s role in the slave trade would have more impact than if it came from an outsider, and it would probably have less consequences. It also has to be remembered that the Liverpool press were often not to kind to our Welsh neighbours. In 1863, the shoddy ‘Jerry Built’ houses in Liverpool were blamed on an earlier generation of Welsh builders. See my 2017 post Jerry Builder: Origin of the term.

5. After the Jester finished in 1883, Gomer’s name doesn’t appear as a story writer until the mid 1890s. Had he really given up writing for over ten years? Or had he written Liverpool and Slavery?

6. He used another alias in the 1890s

Other contenders for Dicky Sam

For balance, we looked at other local authors that should be considered as being the author of Liverpool and Slavery.

Adam Bowker

The first person we looked at was the book’s publisher, the Liverpool antiquarian Adam Bowker. In 1876 his book ‘Funeral records of Liverpool Celebrities’ came out under his own name. But, Bowker had died in 1883, the year before Liverpool and Slavery was printed and the preface is dated 1884. This still does not rule him out of course, as that would be easy to change. Against this premise, is that Bowker would have been 72 yeas old when he wrote it. Also, if Bowker was the author, it does not explain why Gomer completely disregarded the book, or why his son Edward Bowker didn’t raise any objections to so much of his father’s information being copied by Gomer.

Hugh Shimmin

The Porcupine that used the name Dicky Sam in 1883 was started by Hugh Shimmin (1820 – 1879). Shimmin was another man born outside of Liverpool (Isle of Man) who started off in newspapers but went on to be an author. Like Gomer he was also accused of libel, but in Shimmin’s case it resulted in a prison sentence. Shimmin wrote more on social injustice but below is one example of his writing about the slave trade, published in 1863:

In 1720 this traffic had been abandoned by London. The London dog, grasping at the shadow which he saw in the depths of the South Sea, let fall the piece of black flesh which he had been carrying in his mouth. Bristol would have seized the tempting morsel gladly and run away with it; but Liverpool was then, as she is now, energetic and enterprising. So she cut in and cut Bristol out; and Bristol has scarcely ever held up her head in a decent way since Liverpool carried off the slave trade.

High Shimmin, “The Comic History of Liverpool: Chapter XXII,” Porcupine, December 5, 1863. Via Jessica Moody

Dicky Sam covers the same subject but in a less graphic manner:-

The slave trade was relinquished by the merchants of London in the memorable year 1720, when the South Sea scheme proved the ruin of many opulent individuals. Hence, the traffic to the coast of Africa was engrossed by Bristol, till Liverpool, advancing in wealth, population, and enterprise, endeavoured to participate in a species of commerce, which, however repugnant to the feelings of humanity, was productive of opulence.

Liverpool and Slavery, A genuine Dicky Sam, Bowker, 1884

Shimmin died 4 years before Liverpool and Slavery was published but this does not rule him out entirely. In 1871 Bowker had published a book by James Boardman entitled Liverpool Table Talk a Hundred Years Ago. That was ten years after Boardman had died in 1861. The evidence for Shimmin being Dicky Sam ends there. The evidence for Gomer Williams is far greater.

James Stonehouse

Stonehouse was born in 1809 and died aged 81 in 1890. We know in 1863 he used an alias to write his Recollections of Old Liverpool; by a Nonagenarian. He would have been 75 when Liverpool and Slavery was published. He had published his Streets of Liverpool under his own name in 1870 and briefly covered some apescts of both the slave trade and privateering within it, including:

The last century, was a lawless time in its history, for it

swarmed with fierce privateer’s men, inhuman slavers, reckless merchantmen, and violent men-of-war’s men, who all conspired to make the sailor element of the town “thick and slab.”

But why would a 75 year old author revert to using an alias to write about a subject he had already mentioned in a book 14 years earlier? As with Shimmin, there is no other evidence to link him as the author of Liverpool and Slavery.

Summary

Of course it may never be possible to prove Dicky Sam and Gomer Williams were one and the same. Indeed it is of little importance – apart from perhaps crediting Gomer for both of the two of the most influential and famous books on the subject.

Both works were important landmarks in Liverpool facing up to its shameful role in the slave trade. With several exceptions, both used facts to tell the story, which even in the 19th century was already subject to myths such as large-scale auctions of enslaved people instead of the smaller (but still shocking) sales in coffee houses and brokers’ offices.

Likewise, both have been the source and inspiration to later historians for a century and a half, and are likely to continue to be for generations.

But perhaps instead of Dicky Sam, ‘Denbigh Sam’ may have been more accurate?

Gomer’s descendants

Gomer’s daughter goes to college

Mary Gwednoline was able to benefit from the further education her father never had. In 1892, she was attending the Liverpool College for Girls in Grove Street. On the admission record Gomer’s occupation is listed as ‘Journalist’.

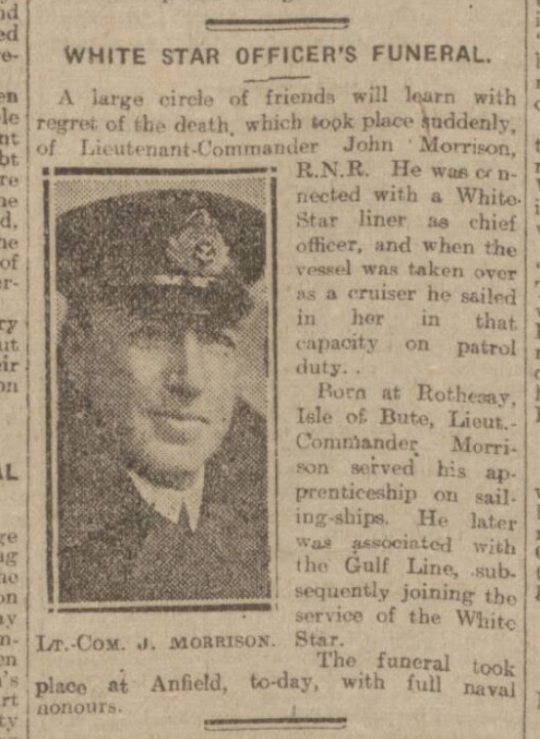

Gomer’s daughter Mary Gwendoline had married merchant seaman John Morison. He was born circa 1867 on the Isle of Bute. He was a chief Officer of the White Star Line. In WWI his cruiser was taken over by Royal Navy and became a patrol boat. He reached the rank of Lieutenant Commander. Mary Gwendoline had to sufferer two bereavements with 12 months, John died in January 1916, the same year as her father.

23 years later in 1939, the register of that year shows widowed Mary Gwendoline aged 64 living in the same house in Redvers Drive. Her occupation is ‘unpaid domestic duties’.

Gomer’s grandson

Mary and John’s son Allan Duncan Morison followed his father’s occupation as a merchant seaman. His Merchant Navy CR2 identity card from 1921 can be seen below:

At the beginning of WWII, the 1939 register shows him as a married man living at 29 Alexandra Drive, Bootle. He is shown as a Deck Officer of the Duchess of Richmond. The register was taken on the 29th September 1939. On the 1st September the ship had been on a summer cruise when when was declared. The ship then became a troop carrier:-

At the beginning of World War II, Duchess of Richmond was taken over as a troop carrier, and began her service in that role with a 7 January 1940 trip from Liverpool to Suez. When the war was over, she was sent to Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering at Glasgow and was refitted in a first-class/tourist-class configuration.

Duchess of Richmond / Empress of Canada (II). Greatships.net

The following year Allan Duncan was Third Officer on the Empress of Britain. This was attacked on 28 Oct 1940 by German Fw200 Condor bombers and then U-boat 32. It was sunk 70 miles northwest of Aran Island, Co. Donegal. It was one of the largest ships sunk by enemy submarines (42,348 tons). Most of the crew and passengers survived, including Allan Duncan. He was awarded a King’s Commendation for his bravery. The ship is also famous for it’s cargo.

Carrying Gold bullion from Africa to America

As well 300 tons of sugar and 300 tons of government stores it was also taking gold bullion from South Africa to the United States. This was rescued as the ship was sinking.

The story of a blazing merchant ship rescuing its African gold from the hands of the enemy would not be out of place amongst the exploits of 18th century privateers in Gomer’s book.

Image: UNDERWOOD ARCHIVES/GETTY IMAGES via The Times.

As well as the King’s Commendation for his bravery, Allan Duncan had the followed service medals: 1939-1945 Star, Atlantic Star, Africa Star (with further clasp), War Medal, Italy Star and Oak Leaf. The Africa Star for the Merchant Navy relates to:

Any Service at sea in the Mediterranean between 10th June, 1940 and 12th May, 1943, and or service in support of the campaigns in Abyssinia, Somaliland and Eritrea. Naval service ashore in the same areas as the army would also qualify. Members of the Merchant Navy who took part in the operations off the coast of Morocco between 8th November, 1942 and 12th May, 1943 would also qualify.

The Italy Star relates to:

Service in the Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea and operations in and around the Dodecanese, Corsica, Greece, Sardinia and Yugoslavia after 11th June 1943

The brave Merchant Navy service of Gomer’s son-in-law in WWI, and then his grandson in WWII, bring to mind a prophetic passage in his book – written 17 years before the First World War began:

For more than eighty years, the merchant navy of the British Empire has sailed in every sea unmolested and unmolesting, until our merchants have become almost oblivious of those contingencies which require to be specially provided against during a naval conflict. Yet do the signs of the times indicate, that in the future, as in the past, the merchant vessels of Liverpool may play a distinguished part in the terrible game of war.

History of the Liverpool privateers and letters of marque with an account of the Liverpool slave trade, Gomer Williams, 1897

Gomer’s Great Grandchildren

In 1938 Allan Duncan had married Kathleen Sutherland. They had a son John in 1939 and in 1942 they had twin daughters Angela and Rosemary – these would be Gomer’s great grandchildren. Allan Duncan survived the war, he died on 3rd August 1954. His wife Kathleen was living at The Sycamores, 49 Orrell Lane, now a children’s nursery. Kathleen passed away in 1994 at Southport.

An appeal to Gomer’s family

To complete our biography we would love to include an image of the man himself. Unfortunately no drawing or photograph could be found. If you are a descendant of Gomer and have any information you would like to share, please contact us at bygoneliverpool@gmail.com.

You are free to share the information but please credit the site and supply a link to the original post.

Credits

Thanks to Mai Roberts whose research on Gomer was of great assistance, in particular the archives written in Welsh that would have been a mystery to us otherwise. Also for the information of Gomer’s death certificate, description from Y Brython and aliases.

We’d also like to thank Alun Jones, editor of Y Casglwr, for sharing the Mai Roberts article and for his assistance in translation. Thanks also to archives the National Library of Wales, the British Newspaper Archive, Find My Past and the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire.

One thought on “Biography of Gomer Williams, Liverpool author and historian”